Yet, the most natural and basic form of language use is dialogue. Traditional mechanistic accounts of language processing derive almost entirely from the study of monologue. phantasmatic deixis distinction the result-ing rule governing the reference of the phantasmatic “I” allows for a homogeneous treatment of ‘I’-tokens in narrative practices spanning the spectrum from fiction to non-fiction.

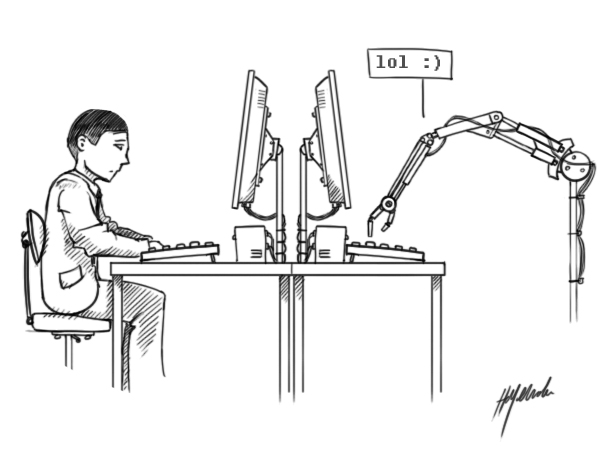

The rule for “I” is revised in light of the perceptual vs. The referential mechanism of the phantasmatic “I”, that is, the “I” used in phantasmatic function, is understood as an instance of imagination-oriented pointing exploiting the phantasmatic context, and not the perceptual context relevant in perceptual uses of indexicals. I propose a model for the reference of “I” based on the distinction between three functions carried out by indexicals in communi-cation, namely, the anaphoric, perceptual, and phantasmatic functions. This view falls short in accounting for all the I-uses in narrative practices, a domain broader than fiction including storytelling, pretense, direct speech reports, delayed communication, the historical present, and any other lin-guistic act in which the referent of the indexical is not perceptually accessible to the receiver. Traditional accounts regard the first-person pronoun as a special token-reflexive indexical whose referent, the utterer, is identified by the linguistic rule expressed by the term plus the context of utterance. We do, however, acknowledge the potential of Turing machines to master dialogue behaviour in highly restricted contexts, where what is called "narrow" AI can still be of considerable utility. Since a Turing machine cannot master human dialogue behaviour, we conclude that a Turing machine also cannot possess what is called "general" Artificial Intelligence. And second, that we do not know how to make machines that possess personality and intentions of the sort we find in humans. We argue, first, that it is for mathematical reasons impossible to program a machine which can master the enormously complex and constantly evolving pattern of variance which human dialogues contain. To pass the test, a machine would have to meet two conditions: (i) react appropriately to the variance in human dialogue and (ii) display a human-like personality and intentions. AI researchers have attempted to build machines that could meet this requirement, but they have so far failed. To pass the test, a machine would have to be able to engage in dialogue in such a way that a human interrogator could not distinguish its behaviour from that of a human being. Since 1950, when Alan Turing proposed what has since come to be called the Turing test, the ability of a machine to pass this test has established itself as the primary hallmark of general AI.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)